Present Estates Pt 2 – Defeasible Fees

Transcript

Second Present Estate - Defeasible Fee

A defeasible fee interest allows the estate to terminate when a given condition occurs.

Welcome back. We have come to our second estate, which is the defeasible fee. Defeasible fees are where things start to become complicated. A defeasible fee is an estate that may last forever, but it may also terminate upon the happening of a stated event. The grant that creates a defeasible fee has to explain what specifically has to occur in order to terminate the grant. As we mentioned when we talked about fee simple absolute, there is a presumption in the law that grantors intend to pass the largest estate that they own. This presumption means that if a grantor is going to attempt to give something less than a fee simple absolute, they have to be really clear about it.

That said, because the law does want to give grantors flexibility, the defeasible fee is a way to give something less than a fee simple absolute. Specifically, the defeasible fee allows the grantor ( the grantor is the seller or the person conveying property) the right to control the use of the property.

With the defeasible fee, the grantor gifts the property to somebody else, but still retains a certain amount of control over how the new owner is going to use the property.

Three Kinds of Defeasible Fees

Defeasible fees come in three flavors. The first is the fee simple determinable, the second is the fee simple subject to executory limitation, and the third is the fee simple subject to condition subsequent. We are going to cover each in turn.

Two Rules of Construction

Durational Language

Look for language about time, like "so long as" or "while."When trying to interpret a potential defeasible fee, there are two important rules of construction. The first is that you need to find clear durational language. Words of mere desire, hope, or intention are insufficient. For example, a grant that says “to A for the purpose of farming” creates a fee simple, not a fee simple determinable. The reason for this is that “for the purpose of farming” is a hope or a desire, it doesn't provide a duration.

However, if we modify the script so that we say “to A so long as the land is farmed,” or we say “to A while the land is farmed,” we have a fee simple determinable and that is because the language “ so long as” or “while” is that key clear durational language that we need in order to create a defeasible fee.

What we're going to see as we dig into each of the three flavors of defeasible fee is that the kind of durational language use almost works as like a magic word. The specific duration or the way the duration is formulated is going to tell us which kind of defeasible fee we have.

Restraints on Alienation

Absolute restraints on alienation are void.The second rule of construction that I want you to pay attention to is about absolute restraints on alienation. We've mentioned that the law presumes that property is alienable. One way that it does that is it will construe grants to preserve the alienability of property where possible, and then absolute restraints on alienation are void. The restraint needs to be reasonable in time and limited in purpose. An absolute restraint on alienation is an absolute ban on the power to sell or transfer that's not linked to any reasonable time or purpose.

For example, to A, but if A tries to sell Blackacre then to B, that grant is going to be void because that's an absolute restraint on alienation. Distinguishing between restraints on use and restraints on alienation can be difficult. Restraints on use are generally valid, even when they all but destroy the owner's ability to sell the land. For example, the grant “to Eagle Academy, as long as the land is used for the education of Eagle Academy students,” effectively prevents Eagle Academy from using the land for anything other than its own educational mission. Still, this restriction is going to be valid because it's focused on the use, not on the ability to sell the land.

To recap, there are two rules of construction to pay attention to. The first is that clear durational language, and the second is restraints on alienation. These are going to help us interpret and analyze the three kinds of defeasible fees.

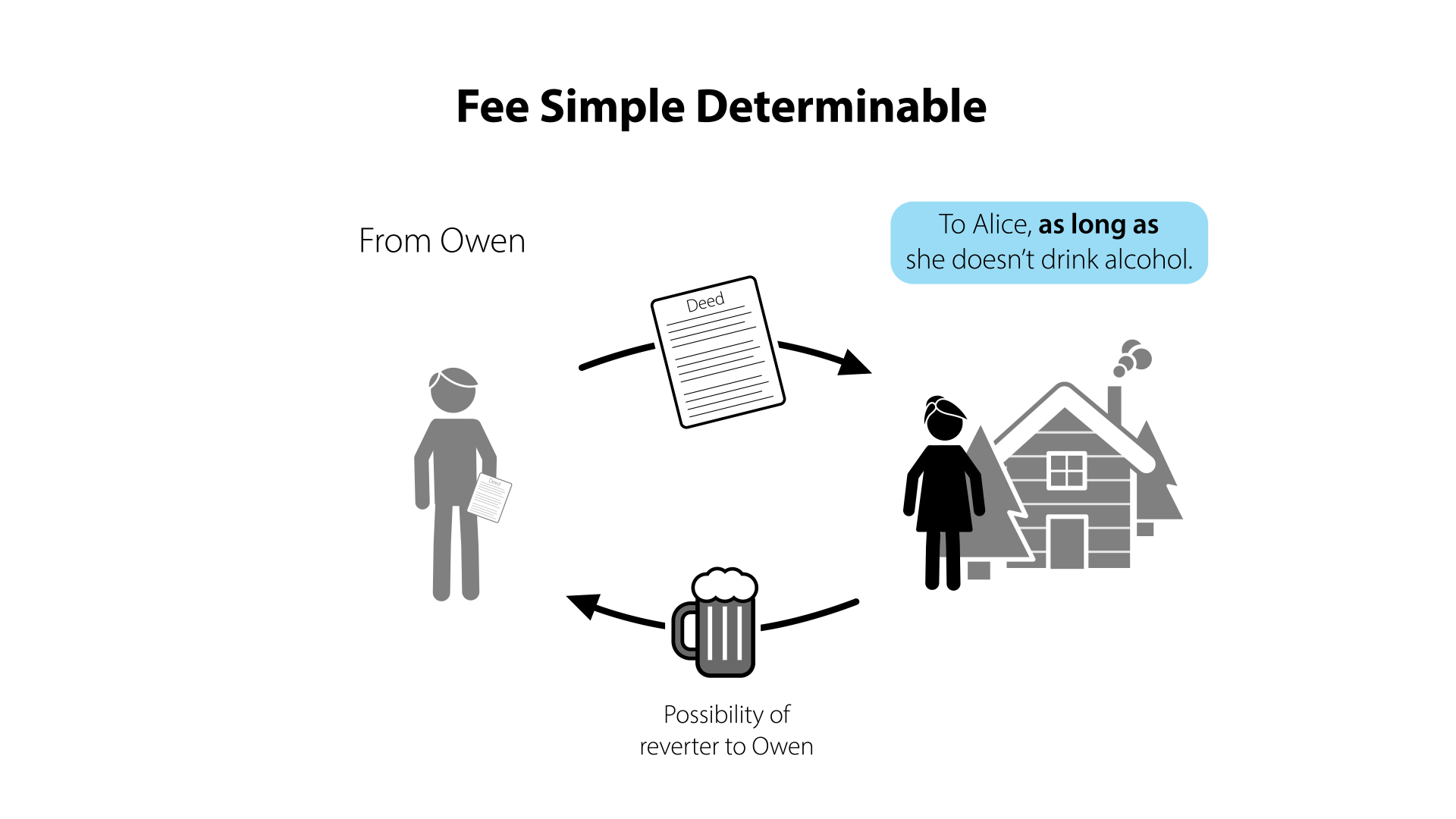

Defeasible Fee Number 1: Fee Simple Determinable

A fee simple determinable, as a present interest, always creates a possibility of reverter, as a future interest.The first of these that we are going to talk about today is the fee simple determinable. A fee simple determinable is an interest where, if the condition that's imposed upon that interest is violated, the grantee automatically loses that interest. That means that the grantor is going to retain a possibility of reverter. We're going to talk about the possibility of reverter when we talk about future interest. For now, what you need to know is that the reverter automatically becomes the present possessory interest if the condition occurs.

If we go back up to one of our examples, “ to A as long as alcohol is never consumed on the property.” If somebody does go and consume alcohol on the property, the grantor is automatically going to become the owner of the property and A is going to have nothing. A is going to have forfeited their interest.

Again, the key to identifying a fee simple determinable is durational language.The thing to look for to determine whether you have a fee simple determinable is the durational language. Think of these as magic words. You want to look out for “so long as,” “ as long as,” “ during,” “while,” or “until.” You are going to be happier if you just memorize this list. When you see this language, you know that you have a fee simple determinable.

Rule against Perpetuities

The RAP does not apply to fee simple determinable estates.A couple of quick notes. The rule against perpetuities is not applicable to the fee simple determinable. This estate, like all other defeasible fees, is devisable, descendible, and alienable, but it's always going to be subject to the condition. The reason why this condition sticks to the grant, even if it's sold or transferred through will or through intestacy laws, is that you can never convey more than you start with.

This idea is sometimes expressed as nemo dat, which is short for nemo dat quod non habet. You might actually see some of this Latin occasionally in practice, but all that you need to know is that you can't give more than you have. Pretty basic concept. If you have a grant that you take subject to a condition, you can only give it subject to the same condition. If A takes Blackacre subject to the condition that alcohol never be consumed on the premises, A can only ever sell Blackacre subject to the condition that alcohol is never consumed on the premises.

Examples

Let's do a couple of examples. First, to A, so long as alcohol is never consumed on the premises, fee simple determinable.

To B, as long as the property is reserved for conservation purposes. Even though we have this purpose language, because we also have durational language “ as long as,” the grant “to B, as long as the property is used for conservation purposes” is going to be a fee simple determinable.

Example three, to C, while used for research purposes. This is also going to be a fee simple determinable because of that word “while.”

Example four here, to D, for research does not create a fee simple determinable because for research is the purpose of the grant, it is not durational.

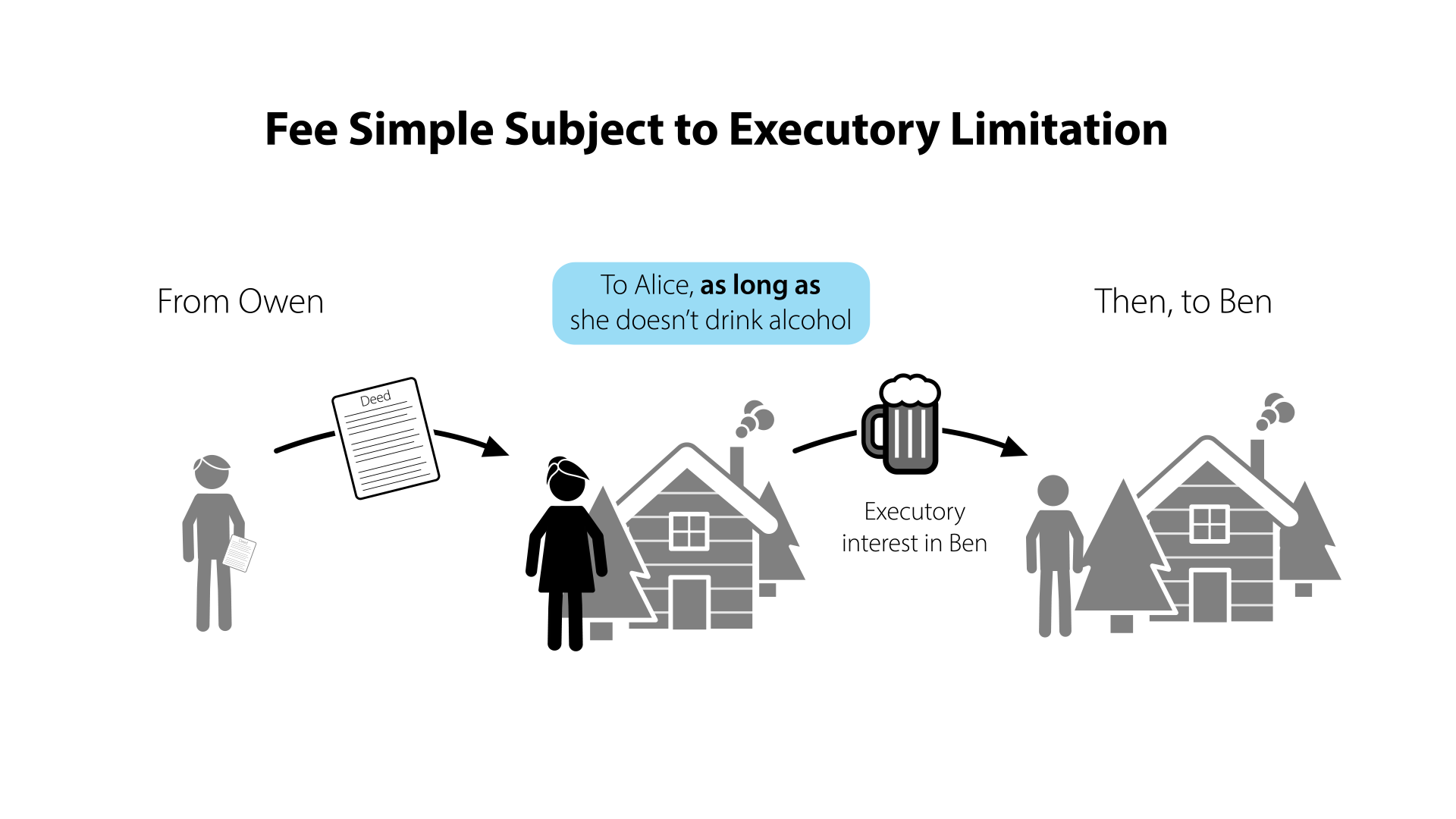

Defeasible Fee Number 2: Fee Simple Subject to Executory Limitation

The difference between this and a fee simple determinable lies in who holds the future interest.The second defeasible fee that we are going to talk about is the fee simple subject to executory limitation. Like the fee simple determinable, the fee simple subject to executory limitation is dependent upon a specified condition that automatically divests the grantees of their interest in the property.

However, in this case, a third party, and not the grantor, holds the future interest. Like the fee simple determinable, the fee simple subject to executory limitation must use clear durational language. Here, you're going to see the same kind of language, “ as long as,” “so long as,” “during,” “while,” or “until.” Here, the rule against perpetuities is going to apply to the executory interest, but if that interest is invalid because it violates the rule against perpetuities, the interest is going to go back to the grantor automatically upon the occurrence of the condition. If the grant to a third party violates the rule against perpetuities, the fee simple subject to executory limitation effectively becomes a fee simple determinable in that the grant is going to go back to the grantor.

Examples

Let's look at a couple of examples. First, to A, so long as alcohol is never consumed on the premises, then to B. This grant should remind you of the example that we talked about when we talked about fee simple determinable. The only difference is that, here, the grantor has specified that a third party is going to get the property upon the occurrence of the condition. That is that language that says "then to B."

Example two, to C, while she lives in Boston, then to D. Notice the durational language here, " while she lives in Boston." Again, this looks a lot like a fee simple determinable, but we know that it's a fee simple subject to executory limitation because instead of the condition giving the property back to the grantor, the grantor has specified that the property goes to D in that language "then to D." Whenever you see this fee simple subject to executory limitation, you're going to see at least two parties in the grant. You're going to see the grantee who's receiving the present estate, but then there has to also be some specified party receiving the future interest, the executory interest.

To recap, the fee simple subject to executory limitation is like a fee simple determinable in that it's a grant in fee simple that is subject to a condition that automatically divests the grantee upon the occurrence of that condition, but instead of the interest going back to the grantor, it goes to a specified third party. That third party is going to hold an executory interest.

Defeasible Fee Number 3: Fee Simple Subject to Condition Subsequent

The difference here is that the grantor must elect to take back the property if the condition occurs.The final defeasible fee that we're going to talk about today is the fee simple subject to condition subsequent. This interest differs from the fee simple determinable and the fee simple subject to executory limitation because the occurrence of the specified condition does not automatically cut the grant short. Instead, the grantor must elect to terminate the grant.

For example, to A, but if alcohol is consumed on the premises, the grantor may reenter. The future interest here goes by a few names, but they all mean the same thing. You might see it called the right of entry, the right to reenter, the right to reacquisition, or the power of termination. If the grantor does want to exercise their right to terminate the interest because a condition has occurred, they must go to court to do so.

This is the key difference between the fee simple subject to condition subsequent and the fee simple determinable. The grantor has to do something in order to divest the grantee of the interest. If the condition occurs, the grantor then has a choice. Do they want to take the interest away from the grantee? Or if they're feeling generous, they might forgive the condition.

The RAP does not apply to fee simple determinable estates.As with the fee simple determinable, the rule against perpetuities does not apply here.

Look for magic words "but if" to create a fee simple subject to condition subsequent.You can identify a fee simple subject to condition subsequent and distinguish it from a fee simple determinable based on the language that's used in the grant. With a fee simple subject to condition subsequent, you're really going to be on the lookout for language that says “but if.”

On the bar, you're often also going to see a specific grant of a right of re-entry. You don't have to see that grant of a right of re-entry, but most of the questions do include it. For example, to B, but if the land is developed, the grantor has a right of reacquisition. That creates a fee simple subject to condition subsequent.

The second example is to C, but if she works outside the home, the grantor has the power of termination. It doesn't matter how the future interest is framed. You want to look for that “but if” language, and just know that there's a lot of different ways that that future interest that allows the grantor to have the option to retake the property.

Special Rules on Grants

Some paternalistic restrictions are legal, but those that penalize marriage or childbearing are void as against public policy.I want to give you a quick note here about some of these conditions that you might see, particularly on fee simple subject to condition subsequent. Note that grants intended to support somebody until marriage or while they are raising a family are generally valid. Sometimes these grants sound troublesome to modern law students.

For example, to C, but if she works outside the home, the grantor has the power of termination. These grants are thought of as grants that support somebody and, therefore, are generally valid. Grants become subject to greater judicial scrutiny and indeed may be invalidated by courts if they penalize marriage.

A grant that said, to C, but if she ever marries, the grantor has the power of termination, is going to be void for violating public policy. It's also possible that grants that penalize having children are invalid. What you want to look for here is whether the grant is attempting to support somebody, even if it's sort of a paternalistic style of support while that person is, say, unmarried or while they are raising children. You want to distinguish those kinds of support grants from grants that intend to penalize somebody if they get married or if they have children.

Distinguishing the Defeasible Fee Interests

To close this section, we're going to talk about how to distinguish among our three flavors of defeasible fees. To recap, the three flavors are fee simple determinable, fee simple subject to executory limitation, and fee simple subject to condition subsequent.

Ambiguous Language

Ambiguous language usually creates a fee simple subject to condition subsequent.First, know that if the language is ambiguous, courts are going to presume that the grantor intended a fee simple subject to condition subsequent. This is because the fee simple subject to condition subsequent avoids forfeiture. Avoiding forfeiture is a common goal throughout property. To be sure, the grantor can cause the grantee to forfeit the property, but the grantor has to make that choice at the time that the condition occurs.

"But If"

These words almost always create a fee simple subject to condition subsequent.Second, if you see the language "but if," you are almost always looking at a fee simple subject to condition subsequent, even if the language in the second part merely names the second grantee or doesn't otherwise specify the future interest. “ But if” is going to be a giveaway that you have a fee simple subject to condition subsequent. For example, to E, but if she establishes her residence elsewhere, then to F.

Third Parties

If a third party receives the future interest, it is a fee simple subject to executory limitation.Finally, if you see a third party receiving the future interest, you are looking at a fee simple subject to executory limitation.

Assessment Questions

Question 1

Question 2

Notes

-

Defeasible fee

-

May last forever or may terminate when an event occurs

-

Allows the grantor to control the use of the property

-

-

Four attributes

-

Devisable

-

Descendible

-

Alienable (with the condition attached)

-

Nemo dat: you can only convey the bundle of rights you have

-

-

Defeasible

-

-

Three kinds

-

Fee simple determinable

-

"To A, as long as alcohol is never consumed on the premises"

-

Magic words: "as long as," "so long as," "during," "while," "until"

-

Not just "for X purpose" without a durational term

-

-

Future interest created: possibility of reverter to the grantor

-

RAP does not apply

-

-

-

Fee simple subject to executory limitation

-

"To A, as long as alcohol is never consumed on the premises, then to B"

-

A specified condition automatically divests the grantee of her interest.

-

Magic words: "as long as," "so long as," "during," "while," "until"

-

-

Future interest created: executory interest in a third party

-

Look for at least two parties in the grant

-

RAP does apply

-

If future interest violates the RAP, the property goes back to the grantor.

-

-

-

-

Fee simple subject to condition subsequent

-

"To A, but if alcohol is consumed on the premises, grantor may reenter"

-

Reversion to the grantor is not automatic.

-

The grantor has the right of reentry/power of termination.

-

-

Magic words: "but if"

-

RAP does not apply

-

-

-

-

What conditions are (and aren't) permitted

-

Grants intended to support someone until marriage or while raising a family

-

"To A, but if she works outside the home, grantor may reenter"

-

Generally valid

-

-

Grants intended to penalize marriage or childbearing

-

Generally void as against public policy

-

-

-

If the grant is ambiguous, courts presume a fee simple subject to condition subsequent.

-

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment. You can get a free account here.