Many people say that the press should not pry into the personal lives of private individuals. ███ ███ █████ ███ ███ █████ ██ ███████ ███ █████ ██ ████████ ██ ███ ██████ ██████ ████ █████ ██ █████████ ███ ██ █ █████ █████ █ ███████ ██████████ ██ ███ █████████ ███ █████ ███ ██ ██████████ ██ ███████ ███ ███ ████ ███████████ ██ ███████ ██ ████████ ██ ███ ███████

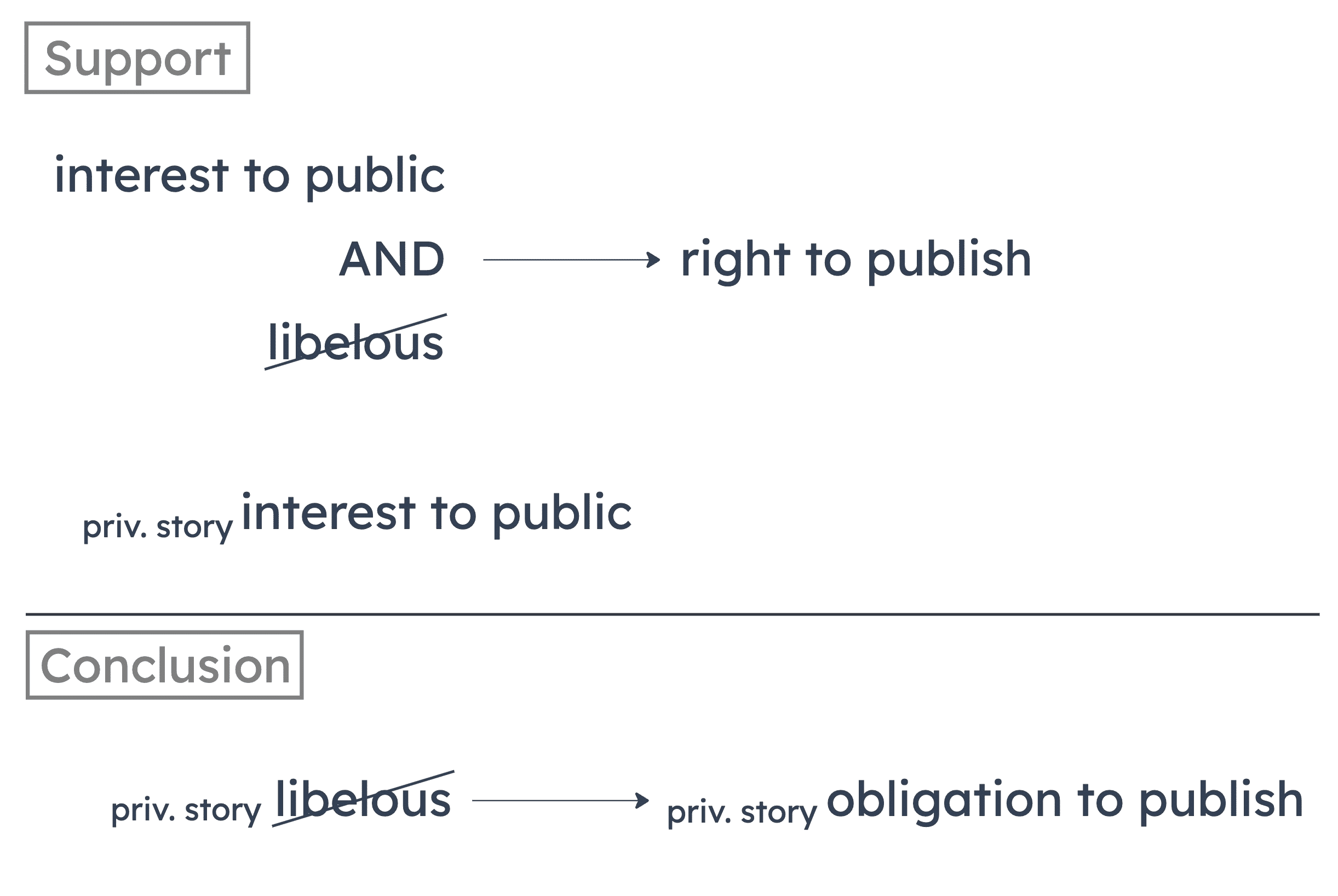

The stimulus can be diagrammed as follows:

The argument presumes, based on the fact that the press has a right to do something, that the press has an obligation to do that thing. The argument gives two sufficient for having the right to publish a story (that the story isn’t libelous and that the story is of interest to the public). When these two sufficient conditions are met, all we can say is that the press has a right to publish a story––the premises don’t say anything about what the press is obligated to do.

The argument's reasoning is vulnerable ██ █████████ ██ ███ ███████ ████ ███ ████████ █████████ ███████ ██████ ████████ ████

the press can ███████ ███████████ ███████ █████ ███████ ███████████ ███████ ██████ ████ █████ ████████ █████

one's having a █████ ██ ██ █████████ ███████ █████ ██████ ██ ██████████ ██ ██ ██

the publishing of ███████████ █████ ███ ████████ █████ ██ ███████ ███████████ ██████ ██ ████████

if one has ██ ██████████ ██ ██ █████████ ████ ███ ███ █ █████ ██ ██ ██

the press's right ██ ███████ ██████ █████████ ███ ████████████ █████ ███ ██ ██ ███████