LSAC requires every student who enrolls in a prep course to purchase a LawHub Advantage subscription for $120/year. The fee goes to LSAC, not 7Sage.

LSAC requires every student who enrolls in a prep course to purchase a LawHub Advantage subscription for $120/year. The fee goes to LSAC, not 7Sage.

LSAC requires every student who enrolls in a prep course to purchase a LawHub Advantage subscription for $120/year. The fee goes to LSAC, not 7Sage.

We’ll teach you everything you need to know—whether you like or not.

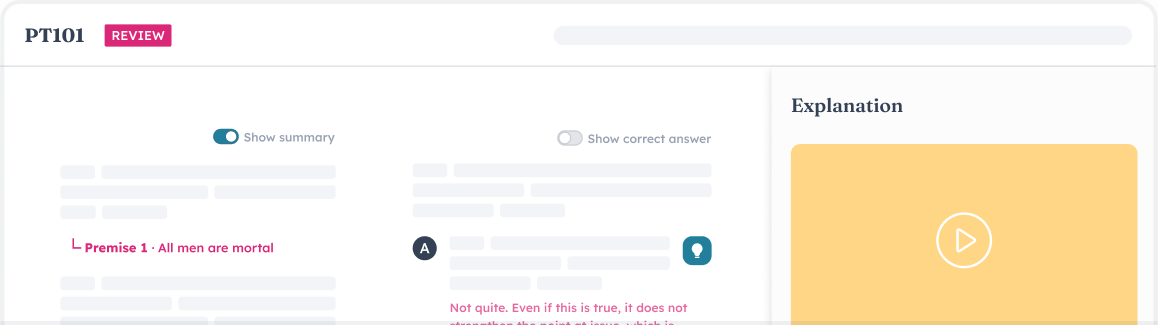

Videos, written explanations, answer-choice snippets, low-res summaries, stimulus highlighting…you probably don’t know what half that stuff means, but you’ll thank us for it later.

12+ classes per weekday. 60+ per week. 3,000+ recorded classes—ready when you are.

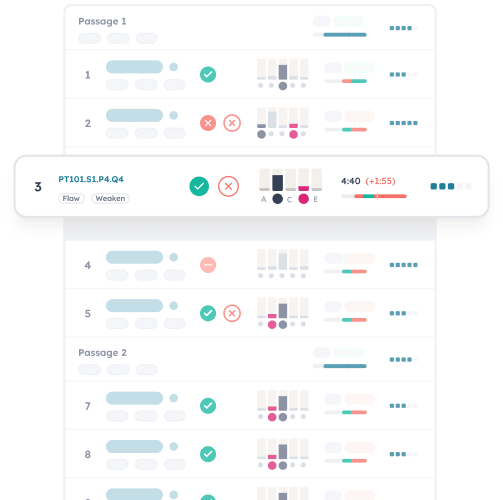

Insanely granular test analytics

Outwork the LSAT. Then try to outsmart it.

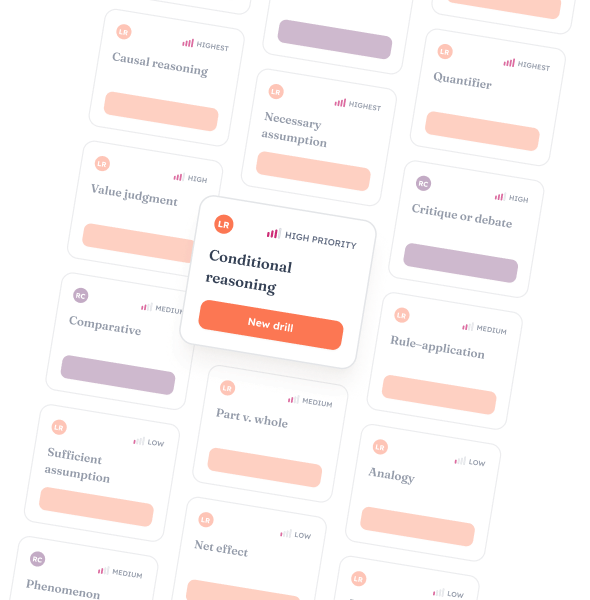

Grind out every point with drills that target your weaknesses

You know those questions you hate? Let’s do a lot of them.

Based on an automated sentiment analysis of Reddit posts mentioning 7Sage, we counted 7,500 upvotes on 336 threads. We think this is a (very) conservative estimate— but we’ll leave it to you to scour the subs and see why so many of our students come from Reddit.

LSAC requires every student who enrolls in a prep course to purchase a LawHub Advantage subscription for $120/year. The fee goes to LSAC, not 7Sage.

LSAC requires every student who enrolls in a prep course to purchase a LawHub Advantage subscription for $120/year. The fee goes to LSAC, not 7Sage.

LSAC requires every student who enrolls in a prep course to purchase a LawHub Advantage subscription for $120/year. The fee goes to LSAC, not 7Sage.

| Compare plans | Core |

Live

|

Coach |

|

Video and text explanations

|

All official LSATs | All official LSATs | All official LSATs |

|

Adaptive study scheduler

|

|||

|

Comprehensive video curriculum

|

|||

|

Analytics & customizable drills

|

|||

|

Discussion forum & study groups

|

|||

|

Import LawHub PrepTests

|

|||

|

Daily live classes

|

|||

|

Class recordings

|

|||

|

Ask a tutor

|

|||

|

Private tutoring

|

|||

|

Personalized accountability emails

|

|||