Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 38 - Section 4 - Question 17

March 16, 2014Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 114 - Section 4 - Question 17

March 16, 2014Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 38 - Section 1 - Question 17

March 16, 2014Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 114 - Section 1 - Question 17

March 16, 2014

A

People who drive infrequently are more likely to be involved in accidents that occur on small roads than in highway accidents.

B

People who drive infrequently are less likely to follow rules for safe driving than are people who drive frequently.

C

People who drive infrequently are less likely to violate local speed limits than are people who drive frequently.

D

People who drive frequently are more likely to make long-distance trips in the course of a year than are people who drive infrequently.

E

People who drive frequently are more likely to become distracted while driving than are people who drive infrequently.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 42 - Section 4 - Question 17

March 5, 2014Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 127 - Section 1 - Question 17

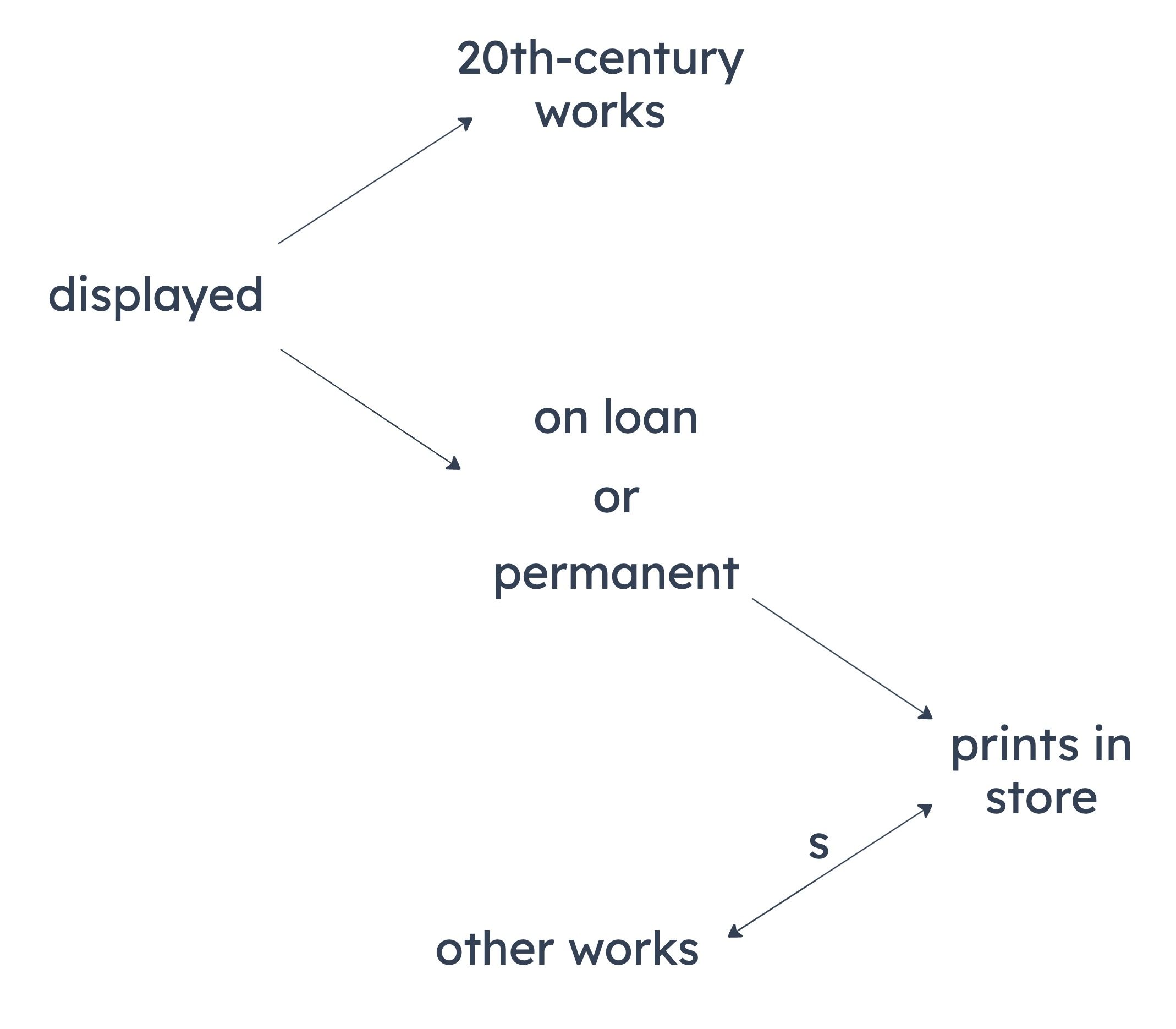

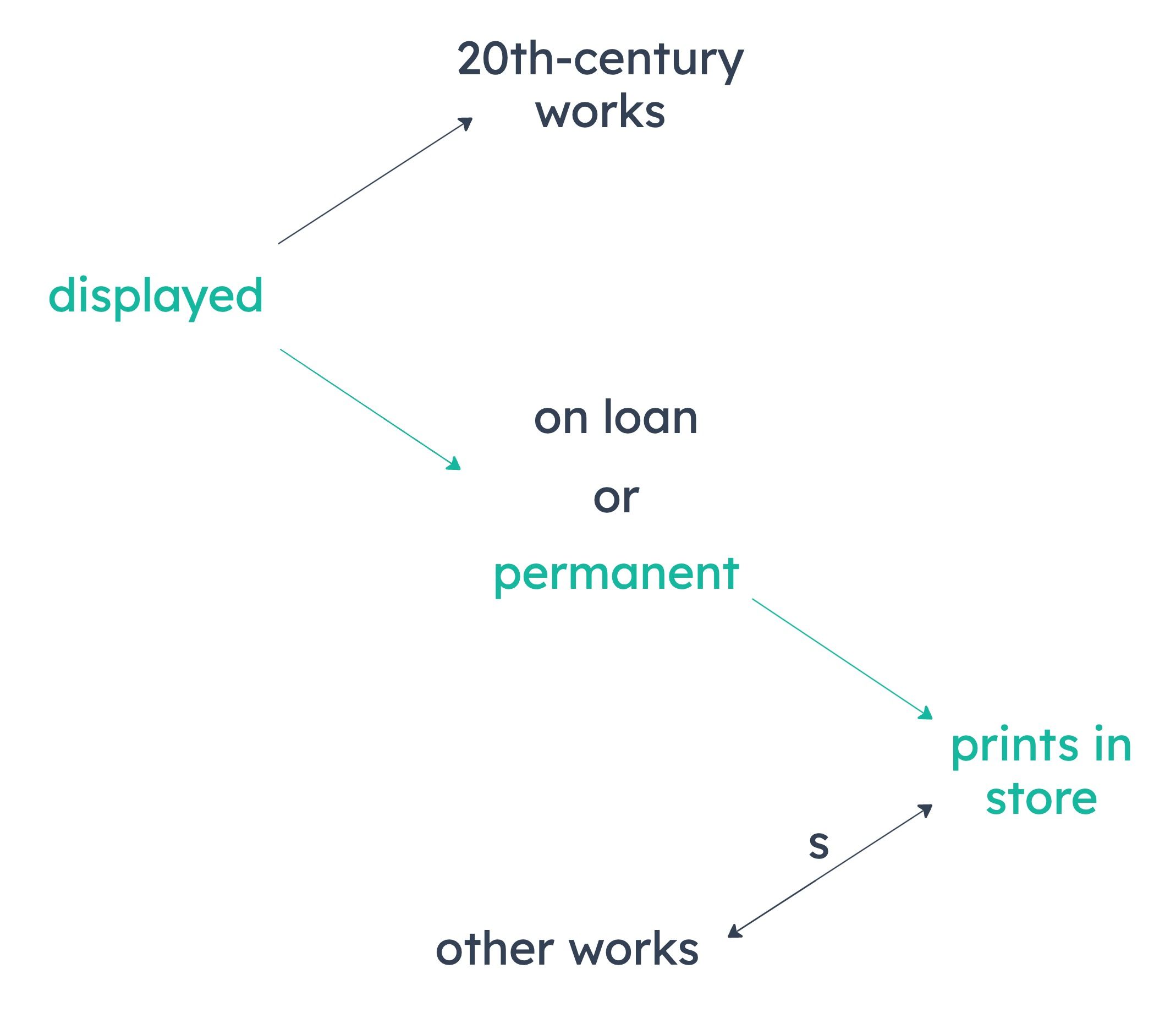

March 5, 2014Curator: Our museum displays only twentieth-century works, which are either on loan from private collectors or in the museum’s permanent collection. Prints of all of the latter works are available in the museum store. The museum store also sells prints of some works that are not part of the museum’s permanent collection, such as Hopper’s Nighthawks.

Summary

If it’s on display, it’s a 20th century work.

If it’s a 20th century work on display, it’s on loan OR in the permanent collection.

If it’s in the permanent collection, prints of it are available in the store.

Some works that aren’t part of the permanent collection are in the store, such as Nighthawks.

Notable Valid Inferences

No particular inference stands out, aside from recognizing the connections between conditionals. If something’s on display, then it must be on loan OR permanent. If it’s permanent, prints of it are available in the store.

A

Every print in the museum store is of a work that is either on loan to the museum from a private collector or part of the museum’s permanent collection.

Could be false. We don’t know about everything available in the store. We know that anything in permanent collection is available in the store. That doesn’t tell us that everything available in the store is on loan or in the permanent collection.

B

Every print that is sold in the museum store is a copy of a twentieth-century work.

Could be false. We don’t know about everything available in the store. There could be many things in the store that are not on display.

C

There are prints in the museum store of every work that is displayed in the museum and not on loan from a private collector.

Must be true. If it’s on display, but not on loan, it must be in permanent. And if it’s in permanent, there are prints available of it in the store.

D

Hopper’s Nighthawks is both a twentieth-century work and a work on loan to the museum from a private collector.

Could be false. We know Nighthawks is not part of the permanent collection. That doesn’t tell us anything else about Nighthawks. It might be on loan, or it might not. It might be 20th century, or it might not.

E

Hopper’s Nighthawks is not displayed in the museum.

Could be false. We know Nighthawks is not part of the permanent collection. That doesn’t tell us whether it is on display. It might be, or it might not.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 42 - Section 2 - Question 17

March 5, 2014Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 126 - Section 4 - Question 17

March 5, 2014

A

does not address the arguments advanced by the politician’s opponents

B

makes an attack on the character of opponents

C

takes for granted that deficit spending has just one cause

D

portrays opponents’ views as more extreme than they really are

E

fails to make clear what counts as excessive spending

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 45 - Section 4 - Question 17

February 28, 2014Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 118 - Section 4 - Question 17

February 28, 2014