Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 14 - Section 4 - Question 20

April 25, 2023This is a flaw/descriptive weakening question, and we know this because of the question stem: “…reasoning is most vulnerable to which one of the following criticisms?”

Let’s take a look at the first sentence. Despite his usually poor appetite, Monroe enjoys three meals at Tip-Top but becomes sick after each meal. Immediately, this sounds like a correlation: the phenomenon of becoming sick occurring with the phenomenon of eating a Tip-Top.

The second sentence is pretty straightforward: it’s a list of each meal he ate at the restaurant. Interestingly, they’re all very large meals, especially for someone who generally has a “poor appetite,” and they all have a side of hot peppers. Both of these look like premises. They’re both statements of facts.

What does our conclusion say? Since all three meals had peppers (premise), Monroe concludes that he became ill solely due to Tip-Top’s hot peppers. Solely? Not only is he assuming causation, but it’s very restrictive. Sure, hot peppers may have contributed to feeling ill, but what about eating this kind of unhealthy food? What about eating this amount of food? What if he’s lactose and fried-food intolerant? The causal relationship he establishes is shaky because “solely” is an unwarranted restriction in the implied causation.

Answer Choice (A) It’s hard to establish whether or not it’s descriptively accurate because “too few” is pretty subjective. We sometimes know after one meal why we got sick. Additionally, he still got sick after each of these three meals, so there must be some reason he’s getting sick. But let’s just say it is accurate. Is this the flaw? No! This isn’t a sample size issue; it’s the restriction in the causal relationships that’s an issue. It could be that hot peppers partially contributed to him feeling ill, in which case 3 meals isn’t “too few.”

Answer Choice (B) This is not correct because it’s descriptively inaccurate. We know explicitly from the stimulus that he became ill after consuming each the meal (read first sentence).

Answer Choice (C) This is not descriptively accurate because, although he may want to continue dining at Tip-Top, there is no evidence of this biasing his conclusion. Also, if he wanted to continue eating at Tip-Top, it would make more sense for him to blame his illness on something outside Tip-Top’s control/menu.

Answer Choice (D) This is descriptively accurate, but it’s not the flaw. Just because hot peppers didn’t make everyone else sick, that doesn’t mean it cannot make Monroe sick. Other people’s reaction to the hot peppers is not relevant to the conclusion Monroe draws, and even if this was established, it would not strengthen Monroe’s position.

Correct Answer Choice (E) It demonstrates that his causal relationship is unwarranted by introducing an alternative cause, which we know is one of three ways to disprove a causal relationship.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 14 - Section 4 - Question 18

April 25, 2023This is a Flaw/Descriptive Weakening question and we know this because of the question stem: “The argument is most vulnerable to criticism on the grounds that…”

With a flaw question, we’re trying to identify reason(s) the conclusion wouldn’t follow the premises. In other words, we’re trying to extrapolate and explain why the stimulus is flawed, and why the premises don’t support the conclusion. Remember, there could be multiple flaws.

The first sentence goes into percentages. Whenever this happens, it’s always a good idea to pay close attention to what subset or group of individuals/items is being discussed. Here, we know the group is voice recording taken from small planes involved in relatively minor accidents. Great! What about this group? Over 75% of the recordings showed that the pilot whistled 15 minutes right before the accident. The rest of this percentage pie? Under 25% of the recordings when planes were involved in accidents did not record pilots whistling 15 minutes before the accident.

Two things should be going through our minds here: first, this sounds like a statement of facts, and is probably going to be a premise; second, this sounds like correlative language. If that’s the case, what can we draw from this statement? Only that these two instances are correlative! Remember that correlation does not imply causation.

The second sentence is very straightforward, probably a premise or context. At this point, it’s okay not to really understand what function it has in the argument; let’s put it aside and return to it.

Now we’re coming to our last sentence, and it starts with “therefore.” If I haven’t seen my conclusion and this starts with a conclusion indicator, I’m praying this is it. And it is! It’s a conditional conclusion, which means that we’re only concerned with instances where the pilot starts to whistle because that is when our sufficient condition is triggered. Okay, now on to the substance of the conclusion. Why should passengers take safety precautions when the pilot starts to whistle? Presumably, there would be a risk. What’s the risk here? According to this argument, and specifically the second sentence, the risks are the minor accidents that small airplanes are involved in.

The argument is making a jump from whistling to the accident but doesn’t explicitly relay what that relationship is. The part where I say “presumably, there would be a risk” is what the argument is assuming as causation. The argument is assuming that since accidents occur in over 75% of the voice-recorder tapes taken from small airplanes involved in relatively minor accidents where the pilot was recorded whistling 15 minutes prior, then it must be that whistling causes those accidents*.*

We know from the core curriculum that this line of reasoning is ridiculous. You cannot imply causation from correlation! There are a thousand different things that could have caused the accident independent of the pilot whistling. And there are many things we can point to that the argument overlooks. For example, what if most pilots whistle during flying—regardless of the size of the plane and the majority of them—and never get into accidents? What if pilots whistle all the time, but different things caused those accidents? The questions are endless. Now that we’ve identified a flaw, let’s get into the answer choices with our two steps: is this answer choice descriptively accurate? Is this the flaw?

Answer Choice (A) Accepting the reliability of the statistics given by the official is descriptively accurate, but this isn’t a flaw. Firstly, we have to accept the premises of this argument, which would mean that we have to accept the statistics. Second, the reliability of the statistic isn’t what makes our conclusion unsupported. This is out.

Answer Choice (B) Descriptively accurate, but not the flaw. This is trying to confuse you by bringing up statistics. This says in 25% of these accidents (where passengers did not hear the pilot whistle), the recommendation (take precautions once they hear whistling) wouldn’t help because they heard no whistling before the accident. So, what? The argument isn’t concerned about the safety of all passengers; it’s specifically talking about passengers who hear the pilot whistle.

Answer Choice (C) This is descriptively accurate, but again, it is not a flaw. Defining what small accidents are is not pertinent to the inadequacy of the support the premise gives the conclusion.

Correct Answer Choice (D) This is saying that the argument is ignoring the percentage of all small airplanes, including the planes that do not get involved in accidents, in which the pilots whistle. What this answer is trying to say is that the argument is only looking at planes that do get involved in small accidents. What about planes that don’t get involved in those accidents – it could be that the argument is overlooking the much more likely scenario that whistling is something pilots do very often during flights, and the correlation between accidents and whistling is a total coincidence.

Answer Choice (E) This is descriptively accurate, but it’s not the flaw. This answer choice forces the argument to consider the proportion of planes that get into accidents; for example, out of 100 small planes, 25 will get into accidents. So, what? This isn’t relevant to the conclusion, nor is it what makes the conclusion unsupported.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 14 - Section 4 - Question 15

April 25, 2023This is a Flaw/Descriptive Weakening question and we know this because of the question stem: “A flaw in the…reasoning…”

With a flaw question, we’re trying to identify reason(s) the conclusion wouldn’t follow the premises. In other words, we’re trying to extrapolate and explain why the stimulus is flawed, and why the premises don’t support the conclusion. Remember, there could be multiple flaws.

The magazine article talks about a new proposal by The Environmental Commissioner and that there is going to be a nationwide debate on them. These new proposals are called “Fresh Thinking on the Environment.” The tone in the next sentence is important: clearly, the article doesn’t think “fresh thinking” can come from the commissioner and therefore the proposal deserves a closer inspection. So far, both of these sound like premises.

The next sentence gives credence to the second sentence we just read: these proposals by the Commissioner are almost identical to Tsarque Inc’s proposals which were issued three months ago.

Before we read the next sentence, what can we conclude from just this information? Well, even though the Commissioner may have believed that his proposals were “fresh thinking,” we can conclude that the title is misleading. We could also say that conversations arising from the debate on the Commissioner’s proposals could be applied to the Tsarque Inc’s proposals.

What does our conclusion say? Since Tsarque Inc’s pollution is an environmental nightmare (premise), the magazine thinks the debate on the Commissioner’s proposals can end here. Note that the argument is jumping from Trasque’s actions to the Commissioner’s proposal. It’s fair to draw similarities between the two proposals since we know they’re identical – remember, we have to accept the premises. The problem is jumping from Tsarque Inc’s actions to Tsarque Inc’s/the Commissioner’s the proposal.

This is the problematic assumption: Trasque’s polluting tendencies are reflected in their proposals (and therefore the Commissioner’s proposal). The magazine article is using the actions of the company against the proposals, even though the content of the proposals could have nothing to do with those actions. In other words, this argument has an “Ad Hominem” fallacy, meaning that an attack directed at the person/organization rather than the position they take in their proposal. The magazine article tried to dismiss the proposal in a roundabout way rather than addressing the content directly. Now that we’ve identified a flaw, let’s get into the answer choices with our two steps: is this answer choice descriptively accurate? Is this the flaw?

Answer Choice (A) This is not descriptively accurate. Two things can be similar without one influencing the other. But for argument’s sake, let’s say this is descriptively accurate – after all, the two people involved in the proposals are close friends. Is this the flaw? Is the reason the argument is flawed because it assumes these influenced one another? No! The argument wants to dismiss the commissioner’s proposals by attacking Trasque’s actions, whose proposals (which are the same as the Commissioner’s) may not have any similarities to their actions.

Answer Choice (B) This is not descriptively accurate - nowhere in the premises do we see distortion.

Correct Answer Choice (C) YES! This is perfectly describing what ad hominem fallacies are.

Answer Choice (D) Emotive? There is no controversial language here. The tone suggest the magazine does not like what is said in the proposals, but it’s not using controversial language. This fails the first step - it’s not descriptively accurate.

Answer Choice (E) This is not descriptively accurate. The argument appeals to Tsarque’s actions; the reference to the chief could have been put there to throw us off, but the argument simply does not appeal to the chief’s authority.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 14 - Section 4 - Question 10

April 25, 2023This is a Flaw/Descriptive Weakening question, more specifically, we need to figure out why the therapist’s response to the interviewer is flawed.

Let’s look at what the Interviewer is saying. In his first sentence, he is talking about the therapist’s claims, saying that biofeedback, diet changes, and better sleep habits succeed in curing insomnia. This is a causal claim. In the next sentence, he elaborates on another claim: with rigorous adherence to the proper treatment, any case of insomnia will be cured. Another causal claim. There is a tone clue here: “You go so far as to claim that…” That makes me think this author doesn’t buy the therapist’s claims. I’m thinking these are both premises, since they represent other people’s ideas.

In the next sentence, we see a “yet;” there is a shift. We were talking about the therapist’s claims, now we’re going to be talking about something that’s probably at odds with the earlier claims. Reading on, that’s exactly the case: our author says that some insomniac patients do not respond to treatment.

So far, all of these sentences look like premises. No sentence is providing support to another sentence. The interviewer is outlining the therapist’s claims and then stating a fact. Well, how can we figure out what the argument is saying without the conclusion??

The conclusion here is implicit. We have enough tonal clues and claims to assume what the author probably thinks. His implicit conclusion is: the therapist’s claim (with rigorous adherence to the proper treatment, any case of insomnia is curable) isn’t realistic. Why? Take a look at that last sentence: “…some patients suffering from insomnia do not respond to treatment.”

The therapist’s counter to this is a single, conditional line: when patient don’t respond to treatment, this just means that they are not rigorous in adhering to their treatment. There is no conclusion here; however, we can assume the implicit conclusion is denying the interviewer’s conclusion. Basically, the therapist’s conclusion would be “my claim still holds."

Why is this argument flawed? It’s circular reasoning: he’s repeating a claim the interviewer attributed to him: with rigorous adherence to proper treatment, insomnia is curable. He’s ignoring the evidence that the interviewer puts forth to discredit him and sneakily assuming a causal relationship that isn’t valid.

Two things:

First: when the interviewer says: “Patients suffering from insomnia do not respond to treatment,” he could have been talking about patients who did adhere to the proper treatment rigorously.

Knowing this allows us to understand the possibility of the next point:

Second: the therapist says that if the patients do not respond, it must be because they didn’t adhere rigorously to the treatment. He’s assuming causation when, as we mentioned above, it could be that patients did adhere to the treatment rigorously and there is another reason the treatment was not effective.

There are a couple of flaws here: first, the illicit causal relationship, and second, the circular reasoning. Let’s go into the answer choices, making sure we hit our two-step test: is this answer choice descriptively accurate? Is this the flaw?

Correct Answer Choice (A) Not only is this descriptively accurate, but it represents the issue of assuming causation and circular reasoning. The argument is ignoring evidence that could show that patients were following the treatment rigorously, and asserts his claims as if the disconfirming evidence would not affect the validity of his claims.

Answer Choice (B) This is not descriptively accurate – treatment is used with consistent meaning throughout the stimulus.

Answer Choice (C) This is descriptively accurate, but it is not a flaw. While there could be different causes for different cases of insomnia, this does not mean that the treatment for each needs to be different. This answer choice does not address the issue of why the argument is flawed.

Answer Choice (D) This is descriptively accurate. But it’s not a flaw. The issue at hand has to do with a repetition of beliefs that ignores evidence and implies causation illicitly. Statistical evidence is not a flaw because statistics are not relevant to the kind of flawed support the therapist’s argument contains.

Answer Choice (E) This is descriptively accurate, but it’s not the flaw. Remember, the therapist is only talking about patients who receive and don’t respond to treatment. Everything else is irrelevant to the argument.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 14 - Section 4 - Question 07

April 25, 2023This is a sufficient assumption (SA) question because the question stem says: “conclusion is properly drawn if which one of the following is assumed?”

Sufficient assumption questions tend to be very formal. We’re looking for a rule that would validate the conclusion, specifically by bridging the premise and conclusion through the rule. Not only are we extrapolating the rule from our argument, but we’re plugging that rule back into the argument to make it valid. Our rule/prephrase will look like: if [premise], then [conclusion].

Our first sentence looks like a straightforward premise: visits to the hospital by heroin users increased by 25% in the 1980s.

The next sentence provides a hypothesis/conclusion to the phenomenon: the use of heroin rose in the 80s. The argument wants us to believe that if visits to the hospital by heroin users increased, then use increased. Why should I believe that? There could be a ton of other reasons why this would not be true! Maybe the stigma around heroin use decreased, so people were more willing to go in for help but usage is the same. Maybe that year, they started lacing heroin with something that warranted a visit to the hospital but usage didn’t increase. The list goes on!

What we need here is a rule that discounts all of those possibilities, something like “if hospital visits by heroin users are increasing, the use of heroin is increasing.” Now, if we plug this rule back into the stimulus, in a world in which heroin users increasingly go to the hospital, it must also be true that the use of heroin is increasing. We sandwich the premise and conclusion together in a conditional rule, bridging them to help make our argument valid. (Note that we’re not saying one causes the other, we’re just establishing a relationship between the two).

Answer Choice (A) This answer choice doesn’t address our argument. We’re trying to show that with increasing hospital visits, the use of heroin increases. What does seeking medical care at specific stages of heroin use have to do with increased hospital visits during a fixed period of time? This answer choice doesn’t fit into the argument at all.

Answer Choice (B) This interacts with our argument by pointing out that some of the visits have been made by the same person. This could mean that the number of users and the amount of use is the same, just that some people come in more frequently, which weakens our argument.

Correct Answer Choice (C) This establishes the positive correlation between hospital visits by heroin users and the overall use of heroin.

Answer Choice (D) If new methods are less hazardous, this could explain why use has increased. However, if use is safer, why are hospital visits increasing in the first place? Remember, we need to validate our entire argument, not just the conclusion. This is out.

Answer Choice (E) This could interact with the premise portion of our argument if we assume that they increasingly began identifying themselves as heroin users when they come to the hospital in the 80s, but that’s a big stretch since we don’t know if this has always been the case or if it became a norm in the 80s. Even if we can assume this, it still doesn’t help validate our conclusion. In fact, it could weaken it: it’s not that use has increased, it’s that more people are open about their use of heroin.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT B - Section 4 - Question 08

April 20, 2023Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 105 - Section 4 - Question 08

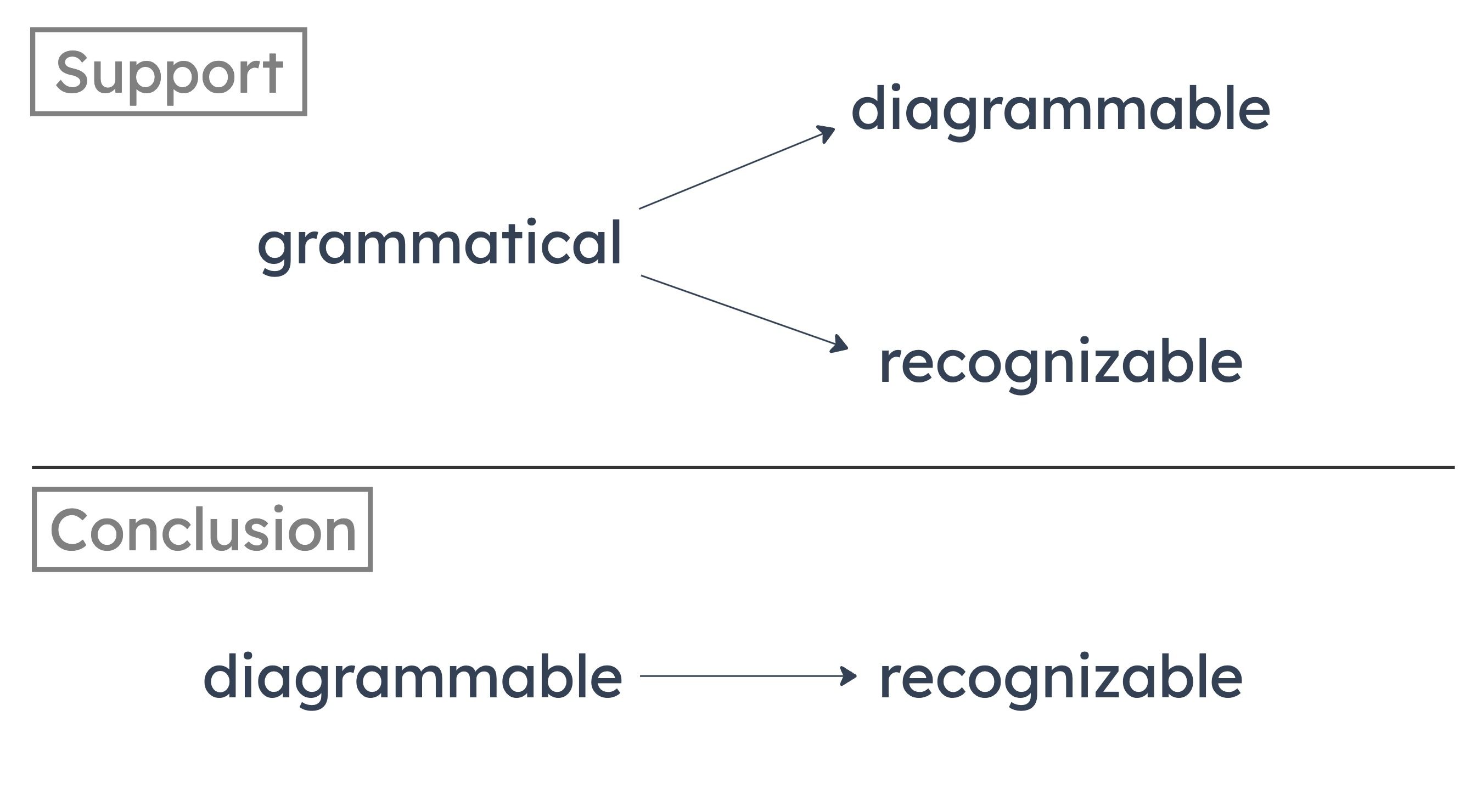

April 20, 2023(1) If a sentence is grammatical, it is diagrammable.

(2) If a sentence is grammatical, it will be recognized as grammatical by speakers of its language.

(3) Speaker X’s sentence is diagrammable.

In other words, he draws a conditional connection between “diagrammable” and “recognizable” when no such connection exists.

A

most people are unable to diagram sentences correctly

B

some ungrammatical sentences are diagrammable

C

all sentences recognized as grammatical can be diagrammed

D

all grammatical sentences can be diagrammed

E

some ungrammatical sentences are recognized as ungrammatical

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 14 - Section 4 - Question 24

April 20, 2023Here we have a Method of Reasoning question, which we know from the question stem: “The argumentative strategy of the investigator quoted is to…”

After correctly identifying the question type we can use structural analysis to describe the Method of Reasoning used by our speaker.

The stimulus begins by providing us with a phenomenon. Disturbances in the desert are found that appear on footpaths that expand for long distances. The question requires us to describe the reasoning used by the quoted investigator. The investigator concludes the discovered paths could not have been incan roads because the roads would be of little use to the incas due to their adjacent placement and abrupt ending point.

Knowing that our correct answer will highlight how the investigator questions the value the roads would have served the Incas, we can proceed into answer choice elimination.

Answer Choice (A) This answer choice is not descriptively accurate because it brings up the idea of counterevidence. Our investigator does not depend on additional evidence to make their claim. Instead the investigator reinterprets the evidence we already have. For this reason we can eliminate answer choice A.

Answer Choice (B) Similarly to answer choice A, this is not descriptively accurate based on the answer choice’s summary of evidence. This answer choice suggests that the investigator provides new information to support their conclusion. Knowing our investigator questions the evidence we already have, we can eliminate this answer choice.

Correct Answer Choice (C) This is exactly what we are looking for. This is the only answer choice that points out the investigator’s questioning of current evidence. This answer choice correctly highlights how the investigator’s conclusion only goes so far as to say what the function of the pathways likely did not serve.

Answer Choice (D) In order for this answer choice to be correct our stimulus would have to refer to the methods used by various investigators to determine their conclusions. Without any reference to the methods used to compile this information we can eliminate answer choice D.

Answer Choice (E) This answer choice is not correct because it claims that our stimulus reconciles two different perspectives. If this were correct we would expect our stimulus to discuss the joining or explanation of a conflict between two different theories. Without this information we can eliminate answer choice E.

Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 14 - Section 4 - Question 09

April 20, 2023Sign up to star your favorites LSAT 13 - Section 4 - Question 01

April 20, 2023Here we have a Method of Reasoning question, which we know from the question stem: “The basic step in Eileen’s method of attacking James’ argument is to…”

After correctly identifying the question type we can use structural analysis to describe the Method of Reasoning used by our speaker, Eileen.

Immediately we should note we have two speakers in our stimulus. That means we need to be on the lookout for two conclusions and two sets of explanations. James begins the conversation by telling us that at their house they have complete personal freedom. On the basis of that freedom, James concludes the government is ignoring the right of individuals to set smoking policies on their own property. This argument is not a good one. Sure, James can do whatever they want in their own home. But boarding a domestic flight does not mean one should receive the same rights as if they were in the privacy of their own home. James has improperly assumed there is no difference between the rights someone has at home versus the rights someone has on an airplane around the general public.

Eileen points out this consideration exactly. In their response, our second speaker highlights what James has assumed. While James has assumed the government has violated a right by not allowing people to do as they please, Eileen points out the difference between actions at home versus on a domestic flight. Smoking on a domestic flight impacts others far more than it would if James were to smoke in his own home.

Knowing that Eileen exactly hits on the assumption of James’ argument, we can proceed into answer choice elimination.

Correct Answer Choice (A) This is exactly what we are looking for! This is the only answer choice that correctly points out how Eileen highlights the apparent differences between an individual at home versus an individual on an airplane. By drawing a distinction between these two locations, Eileen effectively points out the weakness of James’s argument.

Answer Choice (B) This answer choice is not correct. Without the existence of a term being explained in the stimulus we cannot select an answer that suggests Eileen is providing some sort of definition.

Answer Choice (C) This answer choice is not correct. If our correct answer were going to include an analogy, we would be able to identify two items being compared through analogy in Eileen’s part of the discussion.

Answer Choice (D) This answer choice is not correct because of the term contradiction. Contradicting something means our argument provides directly contrary pieces of information. But Eileen does not contradict or say James is wrong – instead, Eileen explains how the base assumption James needs in the first place does not exist.

Answer Choice (E) If this were our correct answer choice, we would see some sort of reference to the motivation of James or others in smoking on airplanes versus in their own homes. Without this information we cannot select answer choice E.